People

- Congratulations to Therese O'Malley, retiring from the Center, National Gallery (1982-2021)

- 2020 Place Maker / Place Keeper Honorees

- Congratulations to Elizabeth K. Meyer!

- Congratulations to Reuben Rainey!

- Meet Betsy Smith, newly appointed president of the Central Park Conservancy as she steps into the shoes of Douglas Blonsky

- As retiring president and CEO of the Central Park Conservancy, Douglas Blonsky leaves behind an extraordinary legacy

- Board Member Robin Karson made honorary member of the American Society of Landscape Architects

- Board Member Laurie Olin is honored by the National Building Museum

- Gold Medal Winner

- Women Who Made New York

- Germany's Green Prince

- 2016 Place Maker / Place Keeper Honorees

- 2015 Place Maker / Place Keeper / Lifetime Achievement Honorees

- Kudos for Board Member Laurie Olin

- Celebrate our 2014 Place Maker and Place Keeper Awardees

- Pillar of New York Award

- Spotlight on Board Members

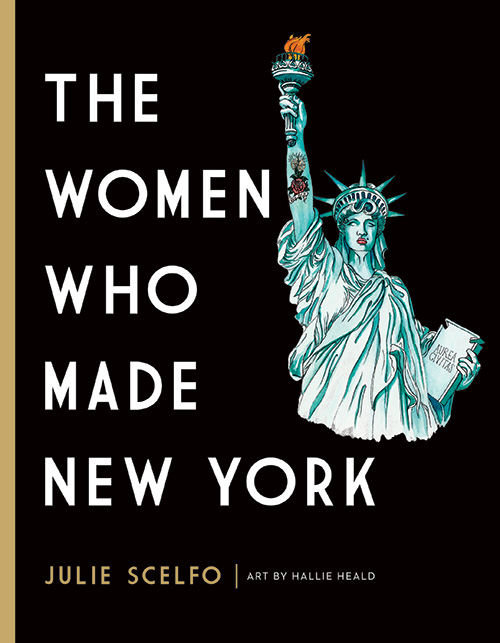

Women Who Made New York

“I never thought of myself as being in the same league as Mae West, Ella Fitzgerald, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis,” Betsy Rogers exclaimed, when she received a complimentary copy of Scelfo’s tribute to an array of heroines of the city. “Of course, praising me is really praising Central Park,” she adds with all due modesty. Besides acknowledging those who are currently in charge of the park’s well-being, she is quick to point out that her very first supporters, when she set out on her improbable mission of saving Central Park from near ruin in the late 1970s, were two other women whom Scelfo hails in her book—high society’s grande dame Brooke Astor and Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger, New York Times matriarch and patron of many city institutions. “Without their belief in me and the support they gave the Central Park Task Force—the predecessor of the Central Park Conservancy—the park’s restoration and management reform would never have gotten off the ground.”

“I never thought of myself as being in the same league as Mae West, Ella Fitzgerald, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis,” Betsy Rogers exclaimed, when she received a complimentary copy of Scelfo’s tribute to an array of heroines of the city. “Of course, praising me is really praising Central Park,” she adds with all due modesty. Besides acknowledging those who are currently in charge of the park’s well-being, she is quick to point out that her very first supporters, when she set out on her improbable mission of saving Central Park from near ruin in the late 1970s, were two other women whom Scelfo hails in her book—high society’s grande dame Brooke Astor and Iphigene Ochs Sulzberger, New York Times matriarch and patron of many city institutions. “Without their belief in me and the support they gave the Central Park Task Force—the predecessor of the Central Park Conservancy—the park’s restoration and management reform would never have gotten off the ground.”

While Rogers is recognized as the woman who resurrected the park from near death over a period of twenty years, she is not a landscape designer per se; the foundation of her career is in fact a literary one. Indeed, it was her second book, Frederick Law Olmsted’s New York, following on the heels of her first, The Forests and Wetlands of New York City, that engendered her passion to make people realize that Central Park is not simply a big urban playground but a great work of American art. “Call me a zealous nut,” she says. “I couldn’t let the citizens of New York ignore this tremendous cultural asset. The outlines of Olmsted’s genius were still there, and while park preservation in the twenty-first century can’t—and shouldn’t try to—precisely replicate the original landscape, the overarching motive of Olmsted and his collaborator Calvert Vaux to create an oasis of nature and picturesque beauty as a respite from the noise and bustle of the surrounding city is still very much alive. It is the primary principle guiding the work of the Central Park Conservancy, which is why the park looks so beautiful today.”

Harmonizing Olmsted and Vaux’s aesthetic sensibility with Robert Moses’s landscape layer of active sports facilities was the Conservancy’s largest challenge as Rogers and her team of landscape architects set about creating a management and restoration plan. However, by 1996, when the organization was on a firm footing, she was eager to return to her former career as a writer on the subject of place. Thus in 2001 she published Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History, the impetus for her creation of Garden History and Landscape Studies program at the Bard Graduate Center, which in turn inspired the founding of the Foundation for Landscape Studies ten years ago.

Today Rogers’s focus is primarily on the work of the FLS, but she almost invariably starts the day with a two-mile walk in Central Park. “It’s where I do my best thinking,” she says. “More than that,” she adds, “it is for me ‘the place of the heart.’ Every time I hear someone say, ‘I don’t know how I could live in New York without Central Park, I always think, ‘me too.’ But this is a parochial perspective. There are wonderful landscapes that people cherish throughout the world. Nor is Central Park the only great park in New York City.” In her latest book, The Green Metropolis, she describes six others besides Central Park as they are experienced by their regular habitués and stalwart guardians. It is not surprising, then, that Scelfo concludes her laudatory profile with Betsy Rogers’s reiteration of the Foundation for Landscape Studies’ mission, “To promote an active understanding of the meaning of place in human life.”